Micromastering a foreign vocabulary, by Neil Ramshaw

The entry trick is identifying the vocabulary you need.

Consider a spectrum of need with 3 levels of requirement that act as boundaries and a mid-point. Deciding which one is closest to your needs is a good starting point:

1 You are going on a car journey in a foreign country to meet a client where the conversation will be in English. You need a few phrases for potential difficulties that might be encountered on the journey.

E.g., Need help car broke.

2 Be able to talk to relatives over the phone in their first language or to be able to communicate in a hotel or shop.

3 Become fluent enough to talk to friends or colleagues daily in their first language.

In the case of 1, simply getting the words translated and recorded as notes or memorised would be sufficient. One might not even need to engage in a formal course to do this.

Once you get to something like number 2 to 3 the amount of vocabulary needed means that you need to be able to break that aim into specific steps.

For number 2 your first micromasteries would be something like, to learn the vocabulary of pleasantries of your relatives’ mother tongue or the vocabulary of asking for drinks and snacks at the hotel.

For number 3, the best advice seems to be to take advantage of the pareto principle and use the fact that the 1000 or so most common words in a language can give up to 70 – 80 % usage.

The entry trick in this case is to chunk your 1000 words into blocks that are meaningful to your aims.

This could be thematically as in case number 2 above. Alongside this and for people studying in a class, it can be useful to check these 1000 words against the progression of vocabulary that is commonly used to teach language acquisition which looks something like this: Naming objects

Commonly - body parts, classroom/learning, clothes, food and drink, family, shopping, work and travel, days, months, and seasons. This is an area where you can personalise the list more to your needs.

Describing objects - colours, numbers, size, pronouns, and prepositions.

Describing actions

Viewing your potential vocabulary needs as a spectrum in this way, gives you scope to re-interpret your goals as you learn more about them and as circumstances change.You can move your objectives about within the spectrum as needed.

The rub-pat barrier is getting the vocabulary you need firmly into your long-term memory whilst maintaining your interest and persistence.

The multiple exposure and review to the same words that can be needed can present an element of monotony. There are two strands to resolving this.

The first is to use techniques that are currently considered best practice in order to be as effectual as possible and the second is to look for the interest and fun in the process for yourself.

Whilst we know that learning and the role of memory are complex, we have accumulatedsome good empirical evidence of what works.

• Working memory – quite simply don’t overload yourself, recent research shows a working range of 3 – 9 items being presented for most people. Experiment to find out where you are on this scale.The current consensus among cognitive scientists is that, in reality, we do notmulti-task!

• Emotions are the link between semantic and episodic memory. You need to find your own stories, cues, and other ways of stimulating the fun and challenge that can generate an emotional response.

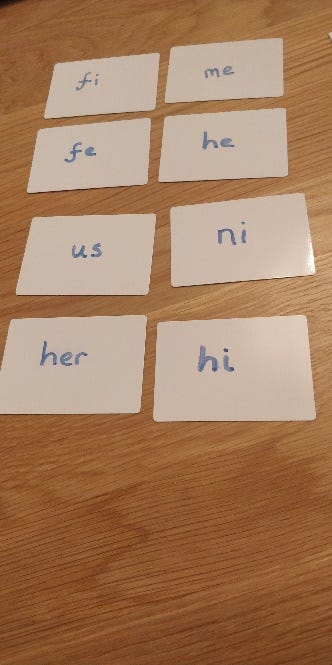

• ‘Multisensory’ works – physically writing, or handling and moving objects, using colour, texture and so on. For example, coloured flash cards or even pebbles or flat blocks of wood that can be written on, can be used to match words. Saying the words as you manipulate them is useful too. Bodily action and singing songs or poems are great memory triggers. This is an area where you can be creative and generate an element of fun. Years ago, when I was teaching my grandson some sight vocabulary, I used to hide the cards around the house. Adults like to move around too.

Example of my working memory optimum with wipeable flash cards

• Spaced practice with active recall is essential coupled with…

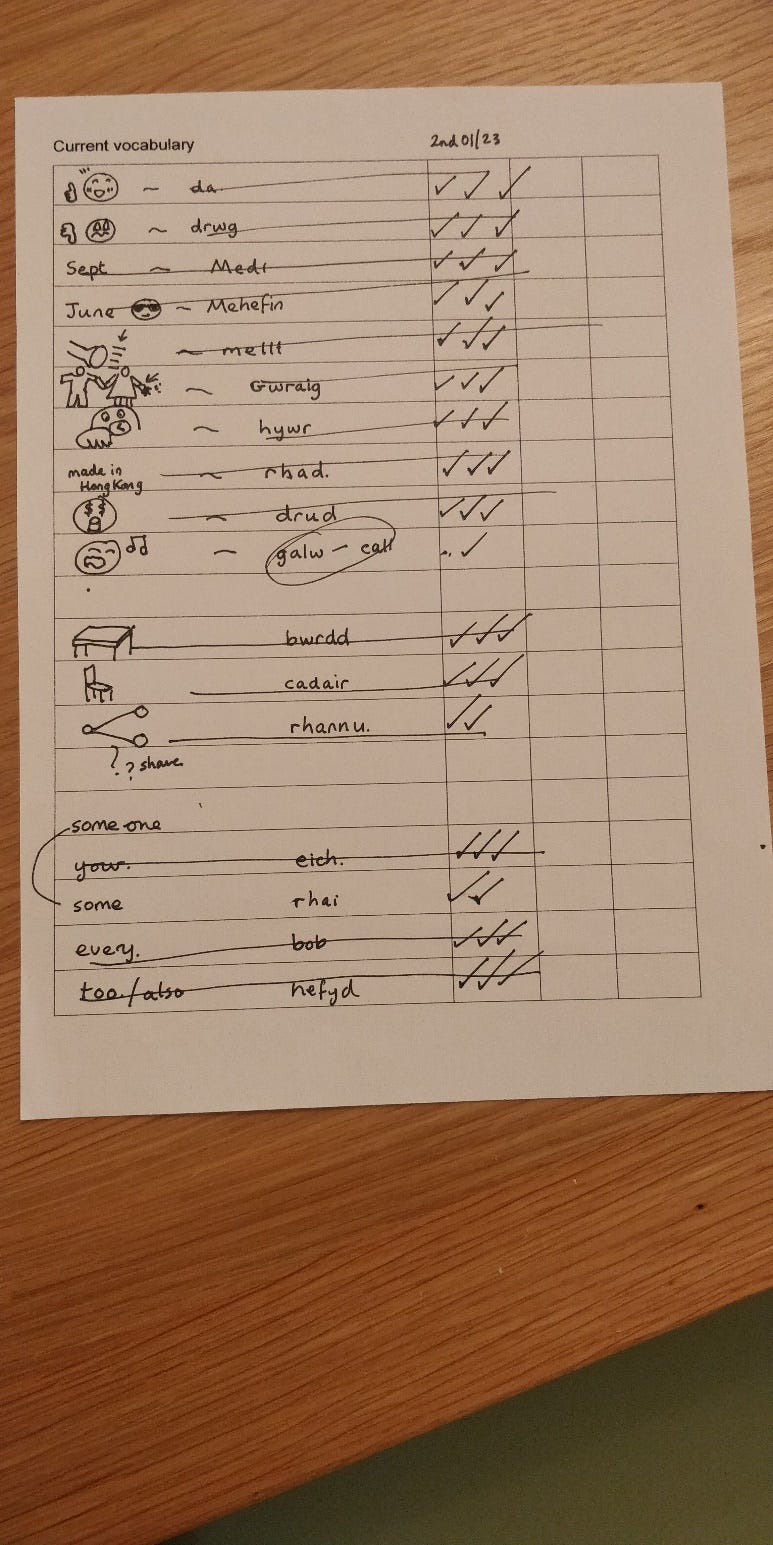

• the importance of knowing what you are forgetting – self testing is better than self-judgement. Keep simple records of what you need to relearn. Then relearn them. Reward yourself, experiment with rewards to find out what works best for you. It is highly likely that you will forget a proportion – it can take up to 16 encounters for some people and some words. It's not that learners are good or bad, some of us just take more time.

Example of simple record keeping of what I don’t know - share and call. Need to check all of them again as its over a month ago.

• There is some debate about the model of ‘tyranny of the mother tongue’ – in which as we age our native language dominates the linguistic map of our mind, It is true that translating from the language we are learning to our mother tongue slows down processing and older learners don’t start to think in the new language quickly. One thing that might be worth doing is quickly replacing the mother tongue word with a picture on your ‘card’. It is not as hard to do with actions and the more abstract nouns and adjectives as you might think. Also making a conscious effort at times as you go about your daily life to spot objects, actions and descriptions and name them directly in the language you are learning.

• Find your desirable level of challenge – if something is too easy it can be easier to forget.

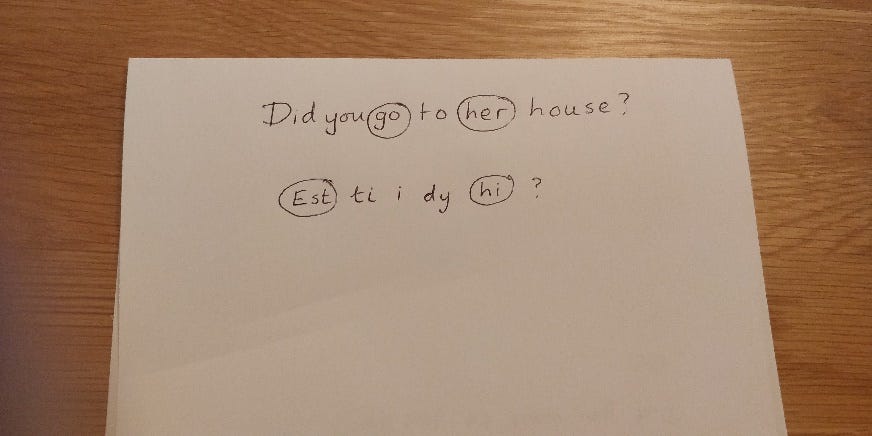

• The challenge is not overloading the working memory but rather comes through the type of recall activity. Active recall, where you remember and use the word in real contexts aids memory, and it is the context where you can experiment to find your desirable level of challenge and interleave them (avoid long sequences of the same activity). More on this in the final newsletter. Simply, what we are describing is using the words that you are memorising in spoken and written sentences.

An example of active recall – where the learned vocabulary really gets embedded by using it. I’ve upped the challenge by also recalling past tense of go with the word her that I am trying to llearn

• Try and make it habitual – have the vocabulary you are working on to hand so you can practice in free moments in ‘non-places.’ Technology on a phone can work as well as this as a notebook. For example, Ankidroid is flash card app that might be easier than carrying a deck of cards whilst on the move.

• Beyond the core words, focus on the vocabulary that you are interested in andwould have something to say about. This is another area where you can take control of your learning and create part of your own curriculum.

• As well as learning individual words start learning short phrases that are used regularly in the language you are using.

Masks and Micromastery, by Robert Twigger

Mask acting is a fascinating subject. When you wear a mask you find, if you are improvising, that your voice, gestures and even thoughts begin to change. You BECOME the mask. It is of course ‘suggestion’- but what does that mean? Actors who don a mask with a reddish somewhat bulbous nose found they couldn’t help becoming domineering and bullying while they acted. Independently it was revealed that the mask for the Kabuki character who is a tyrant- had the same kind of nose.

It’s an extreme version of how actors create character. Malcolm Mcdowell ‘grew’ his whole character in Clockwork Orange from the ironic sneer he used in the earlier movie If. Archie Punjabi said she could only ‘be’ the character Kalinda in The Good Wife TV series when she was wearing the right kind of boots. (Incidentally research has shown that footwear definitely affects the way we perceive ourselves and project ourselves…)

Our ideas of self are not as complex or permanent as we may think. We don a certain persona or mask which we have been given by DNA, upbringing and experience and we may be tempted to think ‘that’s me’. But it is just a mask, no different to the actor’s mask, just a lot more familiar.

How we learn and what we learn is very dependent on what mask we are wearing at the time. The ideal one we might think is ‘learner’ or ‘open minded hard working student’. Though these are not bad, experience shows that trying to copy the externals of someone already successful in the area in which you wish to excel is a better strategy.

I am a fascinated fan of the TV series ‘Faking it’ – where a neophyte has to pass themselves off as a professional in some area after only a few weeks tuition. It’s a rich field and I am sure I’ll return to it at some point again, but in this context what is apparent is how important the details are in appearing competent. In one episode a black lawyer had to become a rapper- something totally alien to his lifestyle. He managed to successfully pass himself off as one, even beating an objectively more skilled rap artist who was neither as tall, imposing or swaggering as the lawyer had been advised by his mentor to be.

I have seen people become highly competent at martial arts- rapidly- when they train exclusively with people much better than them- but only when they copy the details- the way of standing, the way of getting off the mat, a certain look. It seems a personality and a skill come from the outside inwards and only with considerable effort the other way round.

It’s about perception. We learn by looking and observing. But our gaze is usually wrong or misdirected. When we ‘act like the professional’ we swivel our gaze onto the important stuff- and we learn.

In micromastery the ‘entry tricks’ are a way of altering our gaze. So is having a ‘top piece of kit’. Remember that we are like someone driving a WW2 tank- all we can see out of is a tiny slit in front. To see more you have to shift your habitual seat. Or learn how to exit the tank…

Micromastery as the Way of Conscious Growth, by Robert Twigger

Conscious Growth is a term that you see more often these days. At first I wasn’t quite sure what was meant by it, in fact I was a little repelled by it because it seemed new age and I’m fairly averse to much new age jargon.

But after a while and a bit of reading I saw that it was a straightforward phrase- it meant consciously attempt to grow rather than just let it happen at random or not at all.

The word grow and growing were being used to replace learn and learning. And I was all for that. We’ve been told to learn by our parents and teachers since the beginning of our lives and what have we done? For one thing, we had associated learning with school and being ‘serious’. The sense of playfulness and experiment we need when learning are absent or contrived and in reality a bit boring (usually) in school type environments. They have to be- you’ve got an exam to pass junior!

In the world of impro acting Keith Johnston, a director and creator of genius, is famous for telling impro actors to ‘be average’, ‘say the obvious thing’. It’s a wonderful remedy to what we’ve been told far too often: ‘do your best’. When you try to do your best you ‘try’. That’s the problem. When you go out and ‘be average’ you just be. And being is where it’s at.

Grow and growth imply time, watering, feeding, pruning, seedlings, good and bad soil. When we ‘try’ to learn we’re back with the trying- the forcing the pace. Drop down a gear, stop ‘trying’. But even that you have probably heard before. Be average.

In aikido the ordinary teacher will tell you ‘relax’. And of course you tense up. A better teacher might say ‘be as stiff as you can be’- call that 10, now see if you can do an 8 or a 7.

Instead of ‘teaching’, a teacher might think of themselves as a gardener of sorts, there to tend promising seedlings. At first they just need to make sure the seeds have bedded in. The temptation to water and feed is like the temptation to correct a student too early on. All they need is sunlight and good soil and being watched. The main activity of gardening (and teaching) is keeping an eye on the ball. And providing sunlight. And remembering this: things grow. It’s what they do. Everything organic is always growing. Even when some of the outward form is dying off new kinds of growth will be going on elsewhere. In the case of the human being new connections and ideas are happening all the time, even when the person is close to physical death. Their mind is still growing. It can grow consciously or it can grow randomly- reacting to the environment.

Is there a bigger context to this, to the bigger idea of growing in understanding about life and our place in the scheme of things?

I think there is. Think of yourself as being capable of almost infinite growth. You just need to surrender to the possibility of it. This refers to the infinite growth that is somehow in your destiny- not someone else’s. I am not talking about copying another person; doing and achieving what they have done- however attractive- is their destiny, not yours. I think that by emptying ourselves enough of wanting more, by setting ‘empty inside’ as the default rather than ‘fill me up’ we begin to receive subtle information about what we should be doing, what way we could be growing.

Paradoxically this ‘emptying’ can happen when we hit a brick wall in our desire to progress in some way. We find our way blocked, we fail at something or get depressed because of illness or other kinds of incapacity. It is then that the old metaphor of the student being an overfilled jug comes to mind. It is necessary to be empty to receive instruction. But we fill up all too fast. We live in a consumer culture after all, where the default is ‘more’. Bizarrely perhaps- in a culture that demands economic growth we stymy our own growth by continuously dumping rubbish onto the seed beds…it is this insight into growth that I think is worth returning to. Keep returning yourself to ‘empty’, shed all ideas of ‘more’ and wait to see what happens, what seeds start to sprout. If you have externally set-up a learning situation (something you have decided to micromaster perhaps) then the finer instructions, the sense of timing will appear clear to you. You’ll simply know what to do.

People imagine that inner certainty comes from being chock-full of rules and information and confidence- in fact it simply starts with emptying yourself and trusting the universe to speak…

Micromastering the Virtues - Courage. By Chris Watson.

In thinking about courage, it seemed to me that it could be seen as underpinning all the other virtues we are going to examine. We might well need courage to exercise honesty in certain situations, or even to be truly generous, for example.

An error in thinking about courage, is to assume that the courageous feel no fear. This, of course is not true. We all feel fear at times. The courageous are able to continue to act in the face of fear, or quickly bounce back when they have been overwhelmed by fear.

I initially thought the entry trick for micro-mastering courage might be to lean into small anxieties, and this is indeed a useful strategy. But looking a bit more into the neurobiology of fear gave me the idea that we can build our ‘courage base’ with even more frequently encountered circumstances.

The amygdalae, little almond-shaped structures deep in the brain are pivotal in fear processing and their activity is modulated by parts of the prefrontal cortex - the brain area involved in what the great neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky calls ‘doing the right, harder thing’. It turns out the amygdala is also activated by novelty, ambiguity and uncertainty so we can usefully and frequently exercise our prefrontal over-ride of amygdaloid fretting by decisively leaning into any minor event that makes us a bit uncomfortable and inclined to avoidance.

Perhaps embracing conversations you feel like avoiding, changes in routine or work practices, just bearing vagueness or uncertainty without rushing to ‘closure’, or situations like making a complaint about goods or service.

Stepping up a notch, anxiety is the little brother of fear and learning to feel anxiety without avoidance, but also without piling in to get it over with, and continue to act in a deliberate way despite it is hugely rewarding and helpful in building courage. Anxieties are the dumbells in the courage gym. They will feel heavy and difficult to begin with, but you will strengthen and happily move on to bigger ones.

Repeatability comes from working with this small stuff. When we hear stories of courage, we will often find ourselves wondering if we’d have cojones to ‘hide the fugitive from the Nazis’ or some such brave, heroic act. These kinds of events are thankfully rare, but we increase our chances of stepping up by consciously cultivating our courage.

Avoidance----Courage----Recklessness

The rub-pat barrier in developing courage is to hit the right balance between fear and confidence. To get a feel for the sweet spot you can zig-zag between being a little avoidant and a little headstrong and get a sense of the ‘envelope’ within which a properly courageous response abides.

Experimentation – sometimes consciously choose not to act with courage. See what that feels like. There may also be an opportunity to respond to hunches and intuitions. Perhaps if you feel a strong draw to avoidance, see how things pan out and whether the outcome might be better than if you’d been braver

Background support - there is lots of stuff on virtues on Wikipedia and Wikiversity has a short course on developing courage. Ryan Holiday, the modern writer on practical application of Stoic philosophy often has good things to say and he’s done a recent book on courage entitled Courage is Calling.

Now have a go at growing that virtue!