May Newsletter

This month we have a toe into the 'muddy waters of Egyptology' and an upside down look at learning through 'what teachers do.'

Micromaster Hieroglyphics

There are about 7-800 hieroglyphs- that is small pictoids that either represent sounds or things or both. It’s a bit confusing as there is also hieratic which is a cursive unpictoid like written language used for more mundane types of writing, but which works like hieroglyphics too. I always though hieratic came way later but it was actually around in the very early old kingdom- 4th dynasty- the time of the pyramids. I thought at first hieratic would be a way in- but no. It seems hieratic is best learnt by learning hieroglyphics first which if you believe the internet is best learnt by learning Coptic first….no way!

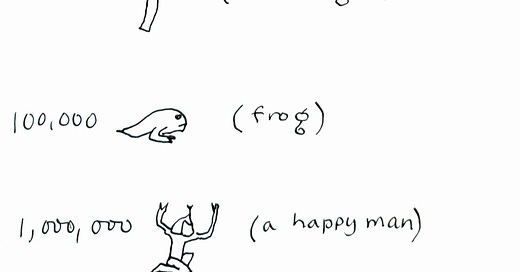

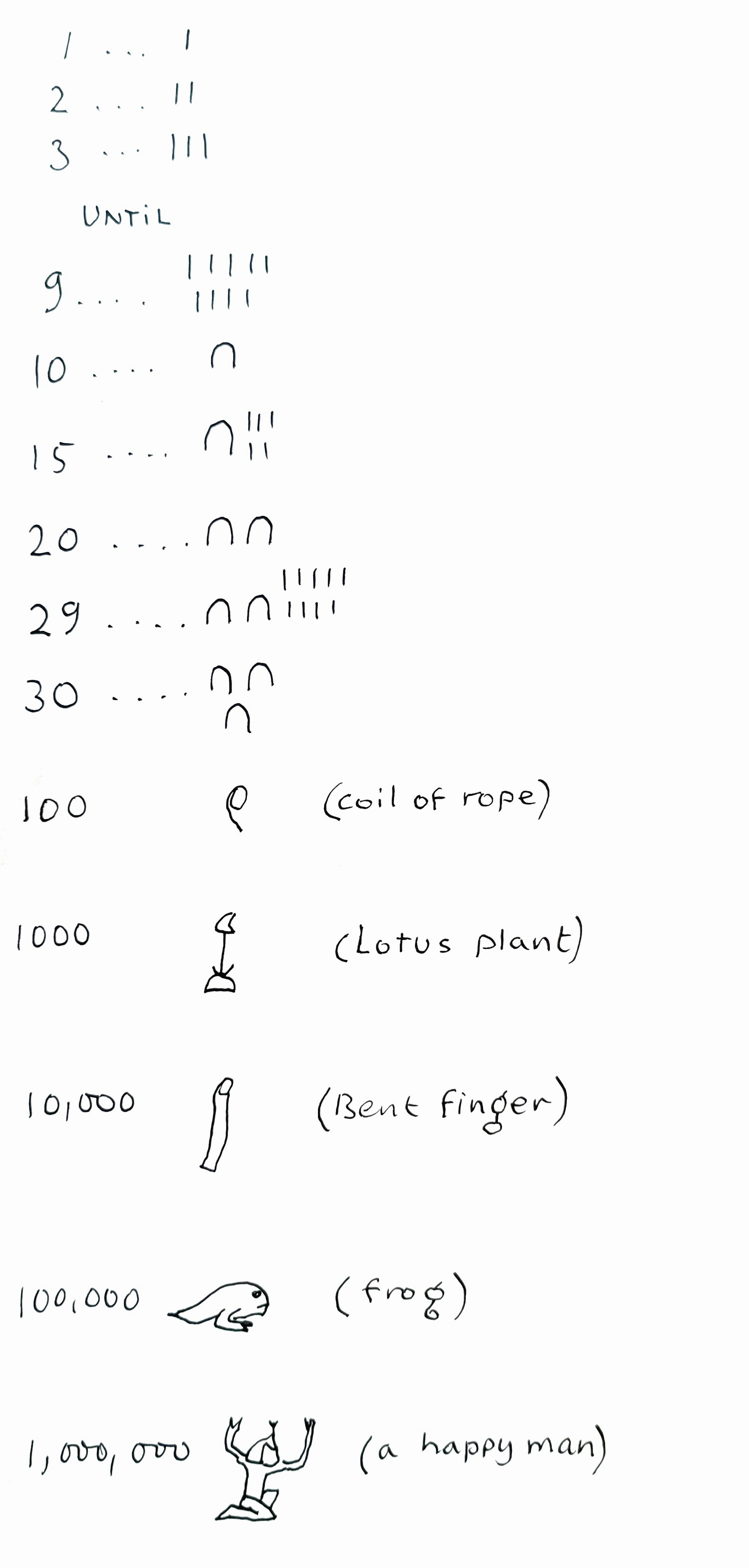

So I decided to learn hieroglyphic numbers as a way in, a toe in the muddy waters of Egyptology. It turns out the ancient Egyptians had a very simple and easy number system from 1 to a million. No zero though, not that a practical person needs zero and the ancient Egyptians were supremely practical- their maths was for building not for impressing each other- like Greek maths with all its axioms that make no sense (to a practical person). The Egyptians even had a workaround for pi, though they never bothered to name it- they just used it. I have the feeling that no one in ancient Egypt would have ‘hated maths’, it’s simply too useful and too obvious to get all worked up about.

Back to the numbers. It was easy enough to memorise that one was a single stroke and ten was an upside down hook sort of thing. To memorise things I use silly images or memorable ones. I saw ten as a bowl you put down over ones. A hundred is an over- lasso of rope- so when you over- lasso a hundred ones you need a rope.(I called it an over lasso to make me recall that the rope went over the top of the loop not under it.)

For a thousand the symbol is rather complicated- it is a complete lotus flower with root and petals. I guess lotuses used to bloom in the Nile by their thousands. This image I broke down into: lefty broken egg-arrow-hemisphere. The petals look like a broken egg shell with the break on the left. The arrow is a root going DOWN to the hemisphere which is the northern hemisphere which is where Egypt is.

Ten thousand is a left bent finger- ‘I told you so’ said the ten thousand know alls in the world.

A hundred thousand is a croaking frog, just crawled out of the swamp where it left 100,000 tadpoles behind.

One million is brilliantly easy- a happy man with his hands in the air- he won the lottery.

Now I can count from one to one million and beyond in ancient Egyptian- it’s a start…

What teachers do - Could you do it for yourself?

Gratitude is due to the late Professor Mary Kennedy of Michigan State University whose work prompted this perspective on learning.

There have long been attempts to consider what teachers do, and long before academics started parsing the practice. Demonstrably, some long established practitioners of practical wisdom have had an excellent working knowledge of this consideration. Academic attempts appear to have been from a limited, ‘dissecting’ approach that tends to become procedural and prescriptive and often fails to consider context. The advantages of Professor Kennedy’s approach are that she focuses on purpose, and is interested in an integrated, dynamic approach that acknowledges the trade-offs that need to be considered in different contexts.

Her approach is to consider teaching behaviours according to 5 persistent challenges faced by teachers. These challenges correspond well with the learning barriers that have been described previously and may well be a useful reframing for readers. In that sense it is not about adding more complexity to learning (“Oh no, I have to learn to be a teacher too?”) rather, it is looking for the things that you are already doing or could do for yourself.

1 Portraying the curriculum

What is meant, is that the curriculum needs to be presented in such as way that makes it comprehensible to the naïve mind. We haven’t considered this as a challenge for the self -directed learner yet. It could be seen as an insurmountable challenge for a novice learner who knows next to nothing about a subject they are interested in. However, many of us are literate and live in an abundant world of texts that give information and increasingly, content that demonstrates skills is also visible to us in video form. And we live in a world where we can see people around us doing things. There is also the knowledge, skills and artifacts that we pick up from our family and culture that we can have as starting points. So, we don’t come to this challenge empty handed – in effect we have been ‘taught’ to some extent, even if not directly.

As many of us are the product of long formal and institutional learning it can be easy to forget that there are other ways of approaching this challenge. People can, have done and continue to learn in much more independent ways than going back to school full time! I emphasise the word ‘more’ here as very few of us are completely isolated and working alone

The problem then becomes how do we make this, that is somewhat inert, into something active and operative?

Or in simpler terms portraying the curriculum can initially be stated as - ‘how do I get started?’

A heuristic that is worth trying is to start in the Applying context but keep it small and ‘humble’ as described in Micromastery. A small scale can prevent mistakes from having more consequential risks to your ability to continue learning whether motivational or financial. For example, I started my working in wood by attempting to make a box with some left-over joinery timber and little more than a saw and chisel. I had a rough idea about the sequence of setting out and cutting the joints from reading. It was a failure, yet I wasn’t too discouraged, I had learnt what I was doing wrong (my paring technique), and the wood even got repurposed. A more ambitious project might have worked better for some people in providing the momentum needed to engage in new learning.

Towards which end is better for you and how can you find out?

Things can begin to get a bit trickier if one wishes to move on from a micromastery start towards a greater depth and breadth of mastery.

Can you recognise when your activities need to change to uplevel your skills and understanding?

What routes are there for you to do this besides going back to school?

This is what a teacher with greater expertise would be able to do. It might not be as difficult as one thinks if one is focussed on a practical activity and want to create something more complicated. This video clip of a man who started his profession by just having a go has a good illustration of how this can work (if you don’t want to watch the whole thing start at about 5.30 and watch up to 7.10, though the video is quite enchanting and covers other aspects being considered.)

2 The second thing that a teacher does is enlist student participation. One element of this is motivation or engagement. The assumption with self-directed adults is that this is irrelevant or a minor problem. Though largely true, it is worth noting previous mentions of one’s potential responses to mistakes and being on the plateau where one’s performances doesn’t seem to be improving. *

Perhaps less well considered is role of a teacher in directing attention? Some teachers do this well through their constant actions and the environment they create that they may well have taught some practices by implicit learning.

Can you remember any examples of this in your own experience?

How did they create a relaxed yet alert atmosphere that allows perception of the apparently inconsequential rather than the over dramatic?

How did they keep you focussed on the detail without projecting too far forward?

It is not just about being able to concentrate (though some things need much attention and few distractions) - most of us can do this with an activity that we find engaging. It’s also about disengaging promptly from the inevitable distractions of life.

Have you learnt or been taught how to actively or consciously do this switching to get back to a state of balance? Which aspects of yourself might be distracting you or make you particularly prone to distraction?

(There is an aspect of learning how to learn here which may start with observing and noting the back and forth of one’s attention. Including its direction (towards yourself or outwards) and which objects which include ideas, beliefs and people.

Are you aware of how distractions outside of learning may be filling you up with preoccupations that might be affecting your apperceptive abilities?

Can you find out what environment is conducive for motivation and learning support, and which also minimises distractions when learning?

Are you aware of these trade offs that teachers face – engaging or fun activities on the one hand which can be less informative and ‘harder’ activities that can be more accurate or promote more learning?

3.The third challenge teachers face is to find out what their students understand, don’t understand or misunderstand so they continually look for ways to expose student thinking.

How are you going to expose your own levels of knowledge, skills and understanding to yourself?

There are quite a few hints in the previous newsletter on internal barriers to learning on the sections on assessment and transfer. (The more in the moment you can do this, usually the more optionality you get.)

If you are engaging learning largely independently, one thing you have that has some advantages is that the distance between the teacher and the student is much smaller than it usually is in a formal setting. One of the challenges that teachers face in such settings is (4), containing student behaviour. That shouldn’t take up as much time and energy as it can in those settings! Another, (5) is accommodating the teacher’s (your) personal needs in addressing the first 4 challenges. Again, this is where the closeness of the ‘teacher’ and student can be an asset.

The final challenge is in finding a practical response to the acknowledgement that there are trade-offs both within and between these 5 challenges that teachers are constantly juggling with. Some have already been described above, and more are listed below -

· What works can become boring (remember we are naturally curious, but curiosity can need maintaining.)

· Steep learning curves (‘challenge’ or how ‘hard’ something is can promote quicker learning but be aware of cognitive overload.) There is a similar trade-off between degree of difficulty and building confidence that was described in the February newsletter. Remember pace of learning can vary owing to a host of variables. Don’t expect pace of learning to be the same all the time. Work to your preferences and strengths AND strengthen the areas you don’t prefer of are not so strong in.

· Application can provide meaning, but can you balance that by directing yourself into little side journeys involving practicing skills. Remember other contexts can provide variety and meaning too (exploration/play.) You will need to juggle time between the different contexts. Similarly, activities that you do as a complete novice are different to those that generate learning as one develops more mastery. You will probably make this switch automatically but being aware of it can be energising (as can being aware of incidental learning!) Remember that bodies of knowledge can change and that aspects of ‘teaching’ itself, can need varying amounts practice.

Finally, keep in mind that you are designed to learn. It is likely that not every barrier will be operating at any given time and that some are not relevant to you at all! The answer to the question in the title is for most people. ‘with a little help, yes.’ When you think about how much you have learnt and realise that these barriers have only slowed down a small proportion of potential learning it is straightforward to remain optimistic!

The points raised in this series of newsletters could be useful in finding your own way of learning, what works for you, rather than the ‘official’ way. See then as a reference tool to return to and that you don’t have to tackle everything at once. Once you have done something potentially quite simple, you have removed something rather than added more complications. And, of course, even spotting your own barriers could be added into ‘locating the fun’ by gamifying it, but simply noting where you get in your own way is all you need to do.