January Newsletter

A 'bumper' issue this month - first a micromastery for learning spoken Arabic from Rob and a reworking of ideas from Rob's blog into two straightforward micromasteries for 'taking care of your time.'

Micromaster spoken Arabic- some preliminary remarks

Learning to speak a new language is hard- and double or treble that for Arabic. Like Chinese and Japanese it has a new alphabet but unlike Japanese it also has word sounds that are confusingly similar to the European’s ears. Not only that, there are new sounds to make that involve glottal stops, deep rolling rr’s in the throat and strangely breathy H’s. It’s a brave new world for sure!

I have made several attempts at learning spoken Arabic and here are my findings for what I believe to be the best way to micromaster it.

First: commit to two hours a day three days a week, or an hour and a half a day five days a week. Yep, people who learn languages put the hours in- there is no other way. For how long- allow three months minimum. You might get to the level you want sooner but it is much better to not feel rushed.

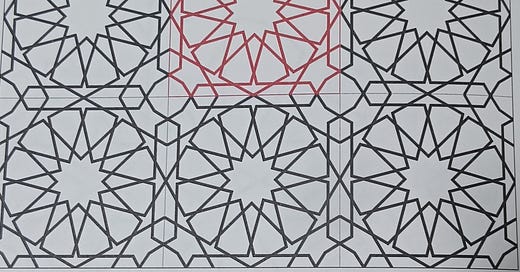

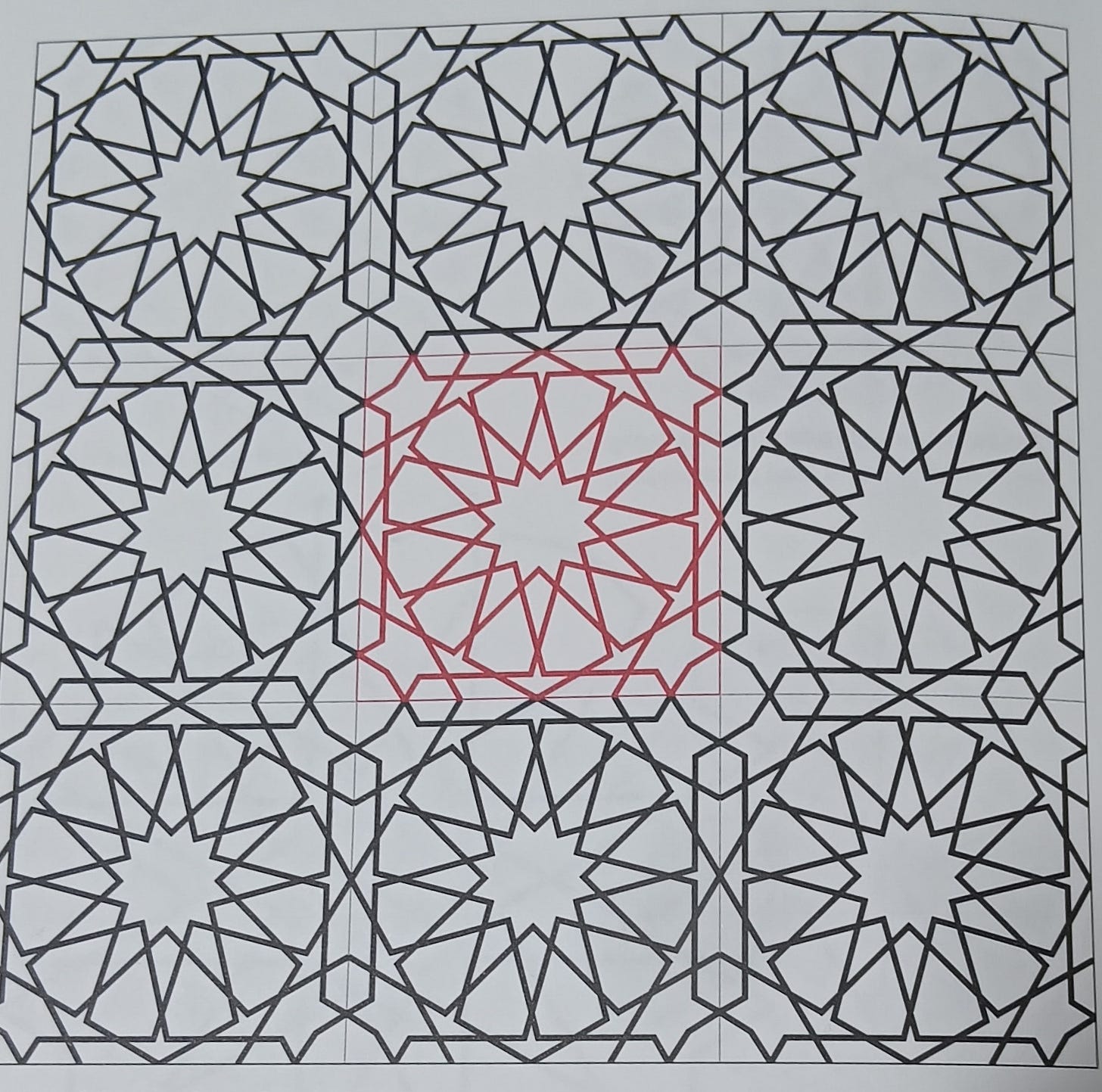

Second: learn the alphabet and the right way to pronounce each letter. Learn all the weird little marks and signs that alter the way you say things. This can all be done at home on your own. Get a nice brush-pen (lots can be found in a good art store) and use it to have fun doing Arabic letters in a swishy calligraphic style. Find an online resource to indicate the correct way to start and finish and you’re away. Get a feeling for the artistry and maybe look at some arty Arabic calligraphy too.

Next is vocab. To remember a word find a memorable (preferably fairly rude or even obscene) image to help you. Write the pronunciation in both Arabic and English. Ultimately you want to be thinking of words purely in Arabic but to get moving I use a hybrid approach- writing my own weird transliteration, the word in Arabic with signs to help pronunciation and then my oddball memory image. After a while you’ll begin to recognise whole words by their familiar shape. If you like a certain letter (I like the snail like letter ‘m’) look for words which repeat it (like mishmash-apricot, momtaz- perfect and momkin- perhaps)- in Arabic these all look very obvious.

Use your own transliteration into English- it will be spot on accurate whereas standard ones never are. An example of my memory method: Low Samaht means if you please. Low and Sam are pretty easy but how on earth will we encode ‘aht’ to make it memorable? This is the main problem so you have to get inventive. I think of the naval word ‘aft’ meaning behind. So Low Sam Aft- is a small sailor called Sam who has pleasing behind to the rest of the navy (the image can even be drawn). But it’s ‘aht’, which sounds like a Scottish ‘Ah’- kind of. So he’s a small Scottish sailor with a pleasing behind- saying ‘please’ for the pleasure- Low Samaht. It sounds and looks a convoluted method and you’ll be tempted to rush. Don’t. Time spent coming up with weird memory images is time very very well spent. For example I just learnt the word for cute (as in baby chick cute) – catcouta (again my transliteration). So easily does this sound like cat-cute-eh? I knew I’d never forget it. This method needs some playing around with but once you get the hang of it you will be able to hold lots of vocabulary in your brain ready for use. You can then practise by writing and drawing out the images again and again on paper and also on cards. Only with practise will you get fast, but if the word is firmly lodged already in your head it’s a big advantage.

I often like to make up a sentence with a rhyme in it. ‘Ousra ti Youssra kibeera.’ This means Youssra’s family is big. Youssra is Egypt’s most famous living film star so it’s a painless and easy way to learn ousra-family, ti-of, and kibeera- large.

If you have no target country in mind, make sure you learn Egyptian Arabic as this is the most widely understood owing to Egyptian films and TV shows. Under NO CICRUMSTANCES try to learn modern standard Arabic or classical Arabic unless you want to read the classics or become a diplomat. For getting around you need street Arabic- which is what Egyptian Arabic is.

Next you need to find your sweet spot for learning. Is it grammar, vocab, songs, pomes or proverbs? I personally love proverbs and vocabulary. These are things I can trundle along learning on my own. If you like songs check out the videos and lyrics of Nancy Ajram songs- they are the very definition of an ear worm- which is great for learning.

Next, keep your ears open for the POWER words. These are words that punch above their weight, that you hear all the time. When you know a power word you can draw a mind map of it to related words. That way you can bag a whole lot of words at once. Such power words include (my own transliteration) lahzra, haardr, keddr, ashen, taini, dowsha, zahma.

For basic grammar go to the rough guide phrasebook for Egyptian Arabic and the lonely planet Egyptian Arabic phrasebook. They aren’t perfect (and some vocab is wrong) but they are very useful and explain in a stripped down way the gist of the grammar- only two tenses really plus a lot of prefixes and suffixes- which makes it conceptually easier to learn. Judicious use of google will find most Egyptian Arabic words- but don’t always believe the first definition you get.

For practise go online and find a teacher using zoom or teams- you can pay with paypal or similar and the price will be around £10-£12 or less an hour. Bargain!

Now get learning- Good Luck!

***************************************************************

‘Being with Time’

In last month’s newsletter we surveyed how we generally perceive and think about time and noted that our perception is subjective and altered by context and our thoughts about time.

Given that our thoughts about time vary, clearly there is opportunity for thinking and perceiving time in different ways. In this newsletter, we would like to consider ways we could rethink about time and how we take care of it. The words time management are being consciously avoided here. You will find numerous words of advice on time management in books and online, but this approach seems to be from a very limited perspective. The perspective is usually that of ‘efficiency’, which has its place in life and to some extent, in ‘taking care of time’, but a limited place.

There are things in life where the value is precisely in the time spent, not how little time is spent. Taking care of time is much broader and aligns much more with our embodied human existence and the need for meaning and a higher identity. This reconsideration of time could provide much more opportunity for flexibility of thought about time by increasing one’s range of ways of thinking about it.

To begin with, I would like to introduce some terms that Rob uses, which I find very useful in making this distinction between taking care of time and time management.

He uses the terms honouring your time, time allocation and time shifting.

Before we get to micromasteries that reflect these terms, a useful approach could be to explore these terms in range and depth – a bit of background reading to become familiar with the topography and confirm some of the realities of this widened field. Equally, if you want to go straight to the micromasteries, they are in part 2 and you can follow up with the background reading and links later.

********

PART ONE

In examining the idea of allocating time and honouring time in more practical detail, it is worth considering whose clock time and timetables we are working to.

Now, living itself makes some demands on our time. Even the wealthiest billionaire who has ‘cashed out’ and can pay to have virtually everything done for them must allocate some minimal time to their own self-care.

Fantasies of a life of total leisure are just that.

Us lesser mortals must also work for a living and have social obligations, and it is worth noting that much of our clock time is based on that. And not everyone has the luxury of meaningful or fulfilling work. Our work-imposed clock time may have less scope for changing the context and is more likely to be in the area where time management and social negotiation will be more useful. There is some scope for changing our inner perception of it which we will come to later, but a sense of realism is needed here before we begin to consider allocating and honouring our time.

It is also worth acknowledging that many of us in the ‘weird’ west are now generally actually working for less time than our predecessors in the 19th century. And yet, a lot of us have an acute sense that we don’t have enough time. I appreciate that this working less is not true for everybody, (I have worked long hours myself) but it may be useful to actually get a sense of the measure of what your obligated time is and be aware that it can change as your life progresses.

It could also be of value to observe and consider how we are filling our time beyond that of work and seeing what the balance is between our obligations and what comes from such things as a need for busyness, FOMO, distraction of our attention and the like, and what are the internal drivers of these for us.

There does also seem to be a tendency in us, that when individual tasks take less time through tools and devices, that we then fill the space by demanding more of ourselves. It does beg the question ‘What are we ‘saving’ time to do?’ Change starts with observation, so it might be useful to take stock of how one uses one leisure time and whether it is relaxing and regenerating or indeed adding to the sense of ‘not having enough time.’

Robert’s blog entry below also gives a sense of what these terms mean and where we are heading with the ideas.

https://www.roberttwigger.com/journal/2017/6/22/rules-or-discipline.html

What do we mean by timeshifting?

In the previous newsletter we looked at the competing timetables problem or the fact that timetables are often out of synch with our human rhythms. This can lead us into two almost opposite perceptions of time - the sense of being rushed and rushing to complete things by a timetable or the sense of waiting for things to start.

In the case of the former, Robert has a great poem in his blog that might resonate with many.

(https://www.roberttwigger.com/journal/2019/10/28/driving-through-rain.html)

There are a couple of approaches to shifting the feelings in this situation. There are times when we need to rush - escaping from danger is one obvious example. But often the need to do something quickly is not so consequential. If the rush really is not urgent, then stopping and taking a wider perspective can help. When I find myself feeling this as I am driving my grandson to school, and we are late (he likes to stick to his routine even if he is running behind time) I increasingly find myself thinking ‘so what if he is late?’ The consequences for him aren’t too harsh. In my case it needs it considerable conscious effort - I don’t find it easy, there is definitely some part of me that is conditioned to be ‘on time’. This taking a wider perspective or ‘reframing’ technique can be used in many situations involving time and a micromastery for entering into this is described in part two.

There is another aspect to timetabled time and a sense of hurry and rush, and that is the notion of productivity. It is an idea that is a big driver of our industrial system. It has its benefits; it keeps prices low for people of less means for example. One problem with it is that we can sometimes apply it to areas of living where it is not needed or indeed is counter to our aims. You will probably recognise the situation where people are rushing in their enjoyment of something that may be better appreciated slowly. You may be old enough to remember the title of the 1969 romantic comedy, ‘If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium’ as one example of this first tendency. (A good insight into the ‘culture’ of the 60’s if you weren’t there, and it features a very young Ian McShane if you are a fan.)

A bit of friction can slow us down and allow us to appreciate an experience, or think, or give us chance to show commitment. Again, a bit of self-reflection as to the necessity or otherwise of our haste is a good starting point.

Another cause of feeling rushed of hurried is caused by our own desire to move quickly through the tasks we don’t value, such as cleaning, preparing food, washing clothes, and perhaps the more mundane aspects of our jobs. We hurry through these activities to reach the ones we hope and expect to give us more value and meaning. This creates a type of in-between time which can also be linked with the state we experience as boredom.

When timetables don’t go to plan or integrate, we can be left waiting, and it can generate a range of emotions such as frustration and anxiety, and one can certainly have the feeling of not appreciating the moment. Being stuck in delayed traffic or arriving too early and having a slice of time in the waiting room are examples of another type of in-between time. (It happens to me fairly frequently as again I have this habit of giving myself plenty of time to get to appointments ‘in case things go wrong’.) You can’t always change the context of these situations, but you can change the way you think about them and the activities that you do in them.

A gentleman called Rory Sutherland has an interesting take on travel that illustrates one way of reframing. Commenting on the costs and benefits of the HS2 project, (an unfinished high-speed rail line in the UK, for any readers unfamiliar with it) he noted that the billions spent on it would at best take 20 minutes off the journey that was only just over 2 hours long. He jokes that for a fraction of the cost, they could have paid male and female supermodels to walk up and down the train pouring out free glasses of Chateaux Neuf du Pape. Passengers would demand that the trains to go slower!

As well as the terms honouring your time, time allocation and time shifting another way of flexibly rethinking one’s approach to time is to consider Iain Mcgilchrist contention that time is (or can be) adverbial, an aspect of being.

‘Time is not separate from events or experience, and like love, which is also no thing, is revealed in and through events – it is, in other words, as I say adverbial, not substantive.’ (From ‘The Matter with Things’.)

So how do we go about changing our perspective on time through micromastery? Some more background reading which can be read after the micromasteries–

https://www.roberttwigger.com/journal/2011/3/19/timeshifting-1.html

https://www.roberttwigger.com/journal/2009/7/17/do-you-have-more-money-than-time.html

********

PART 2

Some time ago, when I first got interested in my perception of time and started thinking and researching, I noticed that Robert had written in his blog some simple activities that could be reformatted as micromasteries. They were written before Micromastery was published and Rob may well have his own perspective on this reformatting to add to at some point. These are two micromasteries that cover some of the points that have been explored in this and the previous newsletter. They complement each other and may well be worth engaging with at the same time.

A micromastery for allocating and honouring time

The premise behind this micromastery is that our time is precious. We have obligations and distractions that call on it. This is one way of ‘taking care of’ time that allows us to navigate these and be able to consciously allocate time in line with our values and goals,

The entry trick

You need look at and to record how you are currently using (or being used by) time. One suggestion I came across answering the question about what one really does rather than what one thinks one does, is to strap a GoPro camera to yourself and look at the recording! But if you don’t have access to one, you just note what you have done over a period. Record Everything. You don’t necessarily need to do this for an extended period. You could use a sampling technique where you monitor say, a day. And then similarly take further samples at different times of the week and year.

From this, you need to get a sense of the time that is obligated – self-care, earning a living, social obligations. Then you need to look at the time that is ‘left-over’. How much of that is spent on what you want to do or what you think you do? How much of it is spent on distraction by what is convenient or available when your energy is low? Use some of the categories that were outlined in Rob’s blog (rules or discipline above) and your own to get a sense for how the time felt and whether it was energising or energy draining. Were the activities ‘prime-time’, ‘slow-time’, ‘bought-time’, were they rushing or waiting, perhaps even which identity or ‘self’ was involved and so on? Be honest with yourself – this is something that you can’t, in reality, cheat at.

The next step is to decide to allocate your left-over time to those things that you really want to do or think you should do.

Hopefully, the foregoing discussion has shown that you need to start from the acknowledgement that you will never have enough time to do everything you might want to do so you will need to discriminate and use your judgement to make choices or priorities when you allocate them to your available time.

Honouring your time is, in its simplest form, sticking to this timetable except for the exceptions discussed in 4) below.

The timetabling and subsequent monitoring of how well you are sticking to it can take many forms and can be over whatever period works best for you. The more simple, easy to access and manage will make the repeatability easier. This can, over time become part of the experimental possibilities. For example, I allocate my time on a daily basis and then review it with some flexibility, sometimes after a few days of sometimes after a few weeks.

For this, I record only the frequency that I do the things on my ‘want to/should do’ list on a simple tally chart. I have a sense of how much time is involved in each activity so don’t need to record that.

Experimental possibilities and background support

1) You may well have a good idea of what length of time is optimal for you for different activities, but if not, experiment. But, be realistic rather than heroic. Also be aware that it may change from time to time. (See 7 below.)

2) When you are allocating your ‘want or think I should do activities’ don’t overdo it, prioritising 4 or 5 is optimal for most people. Of those, perhaps only 1 or 2 should be demanding ‘projects,’ where you are perhaps choosing to develop a good degree of competence or expertise or mastery. Also, you can choose areas in your life where you are not aiming for excellence from yourself, yet you can remain interested in. Thes can be viewed as something like a menu of options that you can choose from as time allows and follow for a bit and then drop in and out of as priorities change (somewhat like micromasteries.)

3) Give yourselves breaks but choose what you are going to do with them. Choose things that really is rest for you, for rests sake. Choose things that fit well with the time you have for the break. You can try different things occasionally too. As well as exploring the extremes of honouring your time (see 4 below), you may well find that balancing that with a bit of built in slack helps you find out the best place for you between these poles. If you build in slack, failing to stick to the allocation engenders fewer negative emotions when you don’t honour your time.

4) You can equally explore the extremes of how ruthless you want to be with honouring your time and this can of course be gamified. You can, for example check yourself for being distracted from some focus very frequently – something like every minute and contrast that with giving yourself an abundance of slack. You do have to make choices and may well have to be very disciplined with distractions – if you know you are not good with self-discipline, then gamification will be a must . And to be disciplined with these, you may need to be inventive with strategies as they tend for many to work for limited periods.

5) A rub-pat barrier is seeing the timetable as something that helps you honour your time and yet being flexible. The emergencies that the timetabled zen monks were allowed to respond to a part and parcel of life itself with all that uncertainty as it unfolds. You will likely be able learn to distinguish them from distractions and from intuitions. What are emergencies are largely your decision.

6) Like any potentially difficult practise, time honouring may well need gamifying in other ways rather than become something you must fight. (Get yourself a nice moleskin diary for monitoring, reward yourself for good adherence, give yourself some timeslots where you can ‘gorge on distractions’ (see it a bit like dieting where you are eating carefully, yet enjoying that food and when you give yourself the occasional day when you eat what you like) etc. And this of course is part of the payoff – you should find yourself spending more time on your chosen activities, having more energy and perhaps learning about and possibly changing your priorities. Also, a sense of reasonableness for you, and not taking things to literally or to absurd extremes is important. After all some distractions can be lifesaving (being distracted has clearly evolved as such) and there may be very good reasons for a bit of procrastination at times. Some reframing may also be useful here in engendering motivation too, as words like discipline can be jarring to our conditioning. For example, seeing one’s time and attention as a precious resource that can allow us to maintain a coherent self and able to act according to a chosen purpose and that some distractions make us servile and are undeserving of our attention. You are being ruthless to protect this resource!

7) Keep monitoring and adapting to some extent at least. You may find that your priorities change as life progresses and your obligated time changes. Important too, is to monitor what gives you energy, what helps you maintain it rather than dribble it away and what lets you release it consciously in ways that you want to.

Another way of reframing time allocation as something serviceable to you, is how it relates to your energy. There is a clear link between the two. When our time is sliced too thinly and we have to make more transitions, these take energy. The uncertainty of waiting time saps energy. Rushing and being rushed drains energy. Distractions create further transitions, as well as being potential energy sinks in themselves. Needing attention takes energy, giving it can generate it depending upon how and what you give it to. Once again keep the monitoring as simple as you can.

8) Do less of the energy draining activities and see what happens!

A micromastery for perceptions of being rushed and having to wait

This micromastery is a way of getting into that widening of perspective that helps when one is rushing (or feeling rushed) and when one is waiting as described above. For those ‘in between’ or ‘nothing’ times which can make up a considerable part of our lives.

The entry trick is described concisely in this post on Rob’s blog from the point ‘back to the taxi’ and the situation was both rushing and waiting, one that I am sure many of us have experienced!

https://www.roberttwigger.com/journal/2011/1/24/living-in-the-moment-2.html

One description of this type of response is being present. It is an enhancement of our degree of absorption in the present moment and it does seem to help us perceive time as passing more slowly.

Experimental possibilities

1) First, you need to notice that your head is full of thoughts and feelings and to switch on your ‘observing self’. This may need experimenting with and practise. The ‘moving on’ is switching your attention away from the preoccupation with feeling rushed or waiting and here in lie some of the experimental possibilities – what can you switch it to? Already mentioned are – focussing on other people in a positive way, appreciating the scenery. What could you switch to in a bland waiting room with no other people?

2) Robert has several more suggestions in his blog posts on Zenslacking and book of the same name. Essentially, when stuck and waiting, some are about learning to do nothing well. One response to doing nothing well is to really relax, make yourself comfortable and do and think as little as possible! Daydream if you want. Ignore any feelings of guilt when doing this! Non sleep deep relaxation is something you may wish to explore for some of such times (It is easy to find on google if you haven’t heard of it.)

3) Another possibility that suits some of these situations (particularly the waiting in between times) is to always have something that you want to do to hand. This links it to honouring your time directly. Easy at home where you can organise your environment for this. Harder whilst outside. I usually have a notebook when travelling, where I can note things of interest, work on creative projects and so on. Better still would be the ability to do it in my head. Can I carry something to ‘work on’ in my head for when I am stuck on my own waiting? Something I need to experiment with.

4) This type of practice can also be exercised in the mundane activities that we sometimes rush through to get to something more meaningful mentioned in the first section. In this case, why not see them as time for practising the focussed and unhurried practise of micromastery or mastery in everything - the mundane (such as washing the dishes) as well as our chosen projects. There is a practise called ‘ichi-go ich-e’ in Japanese culture that you might find worth exploring.

5) There are also some things that you can practise when you are not in those in between times if you desire to explore this further. The suggestion in Timeshifting to sit for 2 hours (you can of course start with less) to gain insights into what your defaults are in these situations, may well allow you to start to generate your own more absorbing different behaviours.

6) You can link this practice to the first micromastery by noting when you are distracted and using the same entry trick to shift back to what you want to do.

A rub- pat barrier is that these activities can become over-conscious. It is worth noting that the present doesn’t have to reduce to a succession of static points but rather a longer or shorter thicknesses of flow. If it becomes over conscious – give it a break.

It is also helpful keeping in mind that ‘being in the moment’ as a practice or state, is a balancing factor (as needed) against spending too much or mis-directed time in the past and future and is not to be taken to extremes.

What you are trying to do (the payoff) is chip away at disabling states of mind at a pace that suits you and actively choose to alter the way you experience things by changing your sense of time or priorities. If necessary don’t try too hard, give yourself more time, build some slack and if needed take a break from it. The initial aim is simply to have something there for when you need it.

May you ‘be with time’ more!

Thanks for this. Incredibly useful stuff.