Micromaster building a coracle

A coracle is the smallest and simplest boat you can build.

It is strictly a one person river or lake craft propelled by single or double paddles.

Originally coracles were made of a woven wickerwork frame covered with animal skins- deer, bison, buffalo and latterly cow and even horse skins were used. Coracles existed all over the world from Tibet to North America where they were called bullboats. In the UK they remain for specialised tasks such as salmon netting, where they manoeuvrability is highly regarded. Nowadays they are made of wickerwork covered with calico or canvas and then waterproofed with bitumen paint.

It’s good to see one in the flesh, so to speak, as coracles are much wider than they seem in pictures. Both the ones I built were really too narrow, not catastrophically, but once I saw a real one in the Pitt Rivers museum I realised why my coracles had been a bit unsteady. The next best thing is to watch videos on youtube of coracles being used on a river. See their size and dimensions. Yours will not be made in such a fancy way though.

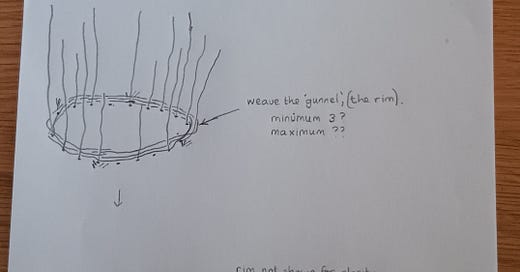

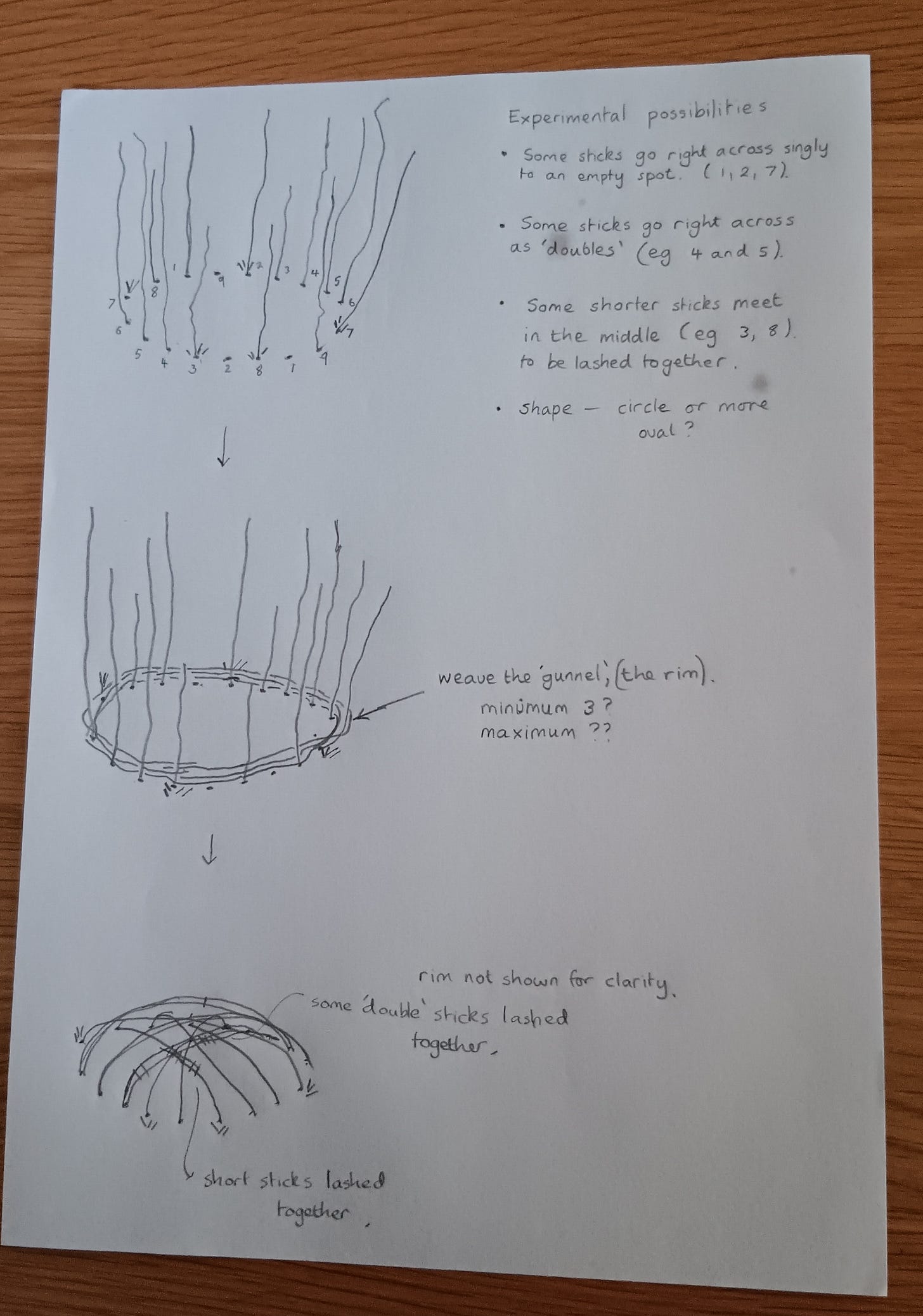

A coracle should be five feet wide at a minimum. For a pure circular one make it a six foot circle. You make it upside down. Plant willow or hazel wands in the ground in the shape you want. Then weave wands in and out of those sticking up to create a band of woven sticks at the base.

You can soak them first and then hold them over a fire to make them easier to bend. Use cable ties to hold them together or string.

Now bend the sticking up wands over so they flatten out and join in the middle to create the flattened upside down bowl shape. Again join with cable ties or string. Next weave sticks in and out of the framework to create more solidity. When you can stand or sit on the upside down coracle it is ready for the seat.

Use a plank to go across the middle, drill holes and cable tie it into position a bit below the top rim.

Now get a big sheet of calico or canvas cloth- it is sold on ebay and amazon. It can be quite thin. Cover the craft with it and put a small stone in each corner and use a loop of string to secure it. This knot will not pull free. Then tighten the string into the frame to create the skin. Do this all around the edge.

Now get some Blackjack or similar bitumen paint (quick drying is a bit quicker but it doesn’t make much difference). Paint three coats and the boat will be ready. You can probably build a coracle in a day or two once you have the sticks.

A double paddle is easier at first, but after a while you’ll find you can use a single paddle effectively too.

Good paddling.

Some good photos of the construction in progress here

https://www.wigtownbookfestival.com/other-pages/events-and-guests

‘Oh, English words find me...’ Ways to Micromastering Writing Poetry

Poetry seems to be an activity of evolving expansiveness with areas of mystery. Thus, it could help in understanding the generality of the underlying template of this specific micromastery, if I share briefly, the context of my interest in both the reading and writing of poetry.

My interest is in poetry that: is based on experience rather than merely conjecture and can offer allusions of that experience, reveals something previously obscured to me, reconciles contradictions and incongruities (‘grim pleasure’ for example) and has good sense. Also, that which shows an acute awareness or observation, sometimes immediacy, and a an interest in things in themselves. We should be lucky to find all that in every poem of course.

In a sense, it is for me any good writing that appeals to the above, and I find it in parts of non-fiction (prose poetry perhaps?) I also find it in poetry of all types, from all ages. And in writing that does not take itself over seriously or leads to an unctuous reading (especially aloud.) In humour too - as Robert Graves has said, ‘a limerick can become delightful in naughty hands.’ Sometimes the coarsest humour and judicious use of profanity can reveal the reality of a situation.

To the task in hand, I will describe a recent experience (and of course part of the entry trick for me is to have an experience that I want to write about) and then go through the writing process to shape it into ‘a poem’.

Writing the event as I would normally speak –

“I was walking through the woods high up on the western slope of the Rhyd y Foel valley. It was the first of February and a was walking my grandson’s dog. It was a cold, dull and still day. I was suddenly surprised by a rustling sound when a breeze blew through the wood. Surprised because the trees were leafless. I stopped, looked around and noticed again the not small proportion of trees in the wood with ivy climbing up the trunks and branches.”

There were three sequential feelings that emerged in this encounter that I will reveal after my attempt to suggest them.

The approach (or entry trick) that I am using at the moment, is to pick one or at most a few forms to try at a time. ‘Use the form to experiment without letting the form use you’.

The form here is a simple rhythmic pattern often used by the ‘Peregrini’ (the monks and other devoted itinerants who settled in the most isolated parts of the British Isles in the early 100’s AD). They had an intense yet receptive interaction with the nature they saw a round them. (Part of the background support for me is the pleasure in the research of reading a range of poetry and beginning to discern some of the forms.)

It seems to work well for short, somewhat charmed, instants such as the one experienced above, rather than say a ballad or a sonnet. We shall see…

Surprising is the rustling, raw and bare the wood.

This is the basic pattern, but it seems too sparse. I need to show that I am in the wood. So, changing it slightly yet keeping the same number of words in the second line my first attempt is to get as much of the sense down in one spontaneous go, using the form

Surprising is the rustling,

in the raw, bare wood.

Halted is the step,

as I sought the cause.

Revealing is the ivy,

cladding trunk and branch.

Pleasing is the source,

that recalls alive is the world.

The repeatability comes in the finishing of the roughly shaped first writing of the poem above.

It is a conscious process of getting the poem in order.

Things to consider include –

Lines beginning with the same words.

Phrases being difficult to say.

Similar sounds too close together

Words not evoking the feeling

Associations too free – the key to which becomes lost on the reader.

Halted is what happened but halting would keep the pattern of sound and cladding breaks the number of words and the rhythm.

Surprising is the rustling,

in the raw bare wood.

Halting is the step,

as I sought the cause.

Revealing is the ivy,

that clads trunk and branch.

Pleasing is to find the source,

that recalls alive is the world.

‘Halting’ and ‘clads’ seem better. But now we have two ‘that’s’ close together and still too many words in the last two lines!

Surprising is the rustling,

in the raw, bare wood.

Halting is the step,

as I sought the cause.

Revealing is the ivy,

which clads trunk and branch.

Pleasing is the encounter,

That reminds unfolding is creation.

Still.

I want to stop there and leave it to sit for a while, maybe discuss it with a critical friend (possible background support.) It has been a largely conscious process of crafting. I am not sure where cladding came from though and it seems to work well, though I don’t want to deconstruct the poem anymore to explain why I think so. I’m not sure about the ‘still’ at the end. I wanted to include using it the sense that the world is still alive, even in winter and something else. But including it in the sentence above would change the rhythm. Also, where it is placed, there is perhaps too much ambiguity. So possibly one last change before I leave it…

Surprising is the rustling,

in the raw, bare wood.

Halting is the step,

as I sought the cause.

Revealing is the ivy,

which clads trunk and branch.

Pleasing is the encounter,

That reminds - creation unfolds still.

The structure has got me started and given me the momentum to keep going with it. I’m enjoying it.

It still needs some work. For a start, I am not happy with the words revealing and pleasing. The structure works as it is. However, I feel that I want to add more to begin with (rather than less and turning it into a haiku) perhaps using the current pattern or feeling free to change it completely. These are the experimental possibilities of the poem writing.

The reason why I want to add more here is because there is another aspect that interests me, explained best by someone who wrote a good number of poems.

‘Poetry is for the poet a means of informing himself on many planes simultaneously, the plane of imagery, the intellectual plane, the musical plane of rhythmic structure and texture – of informing himself of these and possibly other distinguishable planes of a relationship in his mind of certain hitherto inharmonious interests, you may well call them his sub-personalities or other selves. And for the reader, Poetry is a means of similarly informing himself of the range of analogous interests hitherto inharmonious on these same various planes.’ (Robert Graves in ‘On English Poetry, 1922)

Such poetry often demands new readings and there doesn’t seem to be enough content or enough ambiguity in this to draw the reader back – it is almost too clear at the moment. This is not ambiguity in the sense of not being able to pin down the meaning: but in having taken the trouble to not pin the meaning down too closely. A demanding balancing act (definitely a rub pat barrier). (Also, since starting writing this, I have found that the ivy itself is an indicator of something about the temporality of the wood and I now want to try and weave that in too.)

I hope to share further progress in a subsequent newsletter.

[The three feelings I wanted to show were, the initial surprise, mystification perhaps unease at hearing the rustling (because I ‘knew’ on one level I should not be hearing it), the pleasure or relief of discovering the explanation, of having learnt something, and the third feeling of some broader understanding or realisation, including that nature is still alive, just a bit slower, here in winter.

The ‘Oh English words find me…’ in the title is as remembered from an early English poem that I read in a newspaper article years ago and can’t find again, yet captured my interest.