April Newsletter

Looking at transfer of learning and 'reactance, some overall thoughts about 'barriers' and a note from Robert

The Garden Gate, Epping 1894 Lucien Pissarro

A penultimate look at Manoeuvering with internal barriers to learning

Transfer

If you are involved with micromasteries for fun, this is not something to be overly concerned with as transfer is what deeper learning is about largely. Certainly, if one wants to move to greater understanding and expertise or mastery, and to wider application, then transfer is intertwined in that process.

The current consensus view is that ‘transfer’ of learning takes place when we assess new situations based on previous experiences and apply that learned knowledge, skills and strategies to the new context.

There is a view that it is part and parcel of our everyday thinking where we view situations as extensions of, or similar to, previous situations that we have encountered. In that sense it relates to a concordance between the mental representations of the situations that was described in the October 2024 newsletter which outlined a model for how we process sensory inputs. Where we might distinguish it from such everyday processing, is in the sense that we are particularly focusing on the effective extent to which past experiences affect performance and learning in a present new experience.

There are several perspectives used to study transfer and as many theories as to the process. In a newsletter such as this, it is likely that focussing on results from experience will be more useful. In doing so, however, it is also useful to bear in mind that the results here are mainly based on highly controlled and situated experiments rather than in the everyday world.

What has emerged from research so far is a highly variable and diverse assortment of picture of our ability to transfer.

· Children, adults and novices and more experienced people can show transfer ‘spontaneously’ (which is research term for ‘without prompting’). Sometimes this can occur in a similar fashion to insights and intuitions and sometimes active conscious thought is needed. However, such spontaneous transfer is relatively uncommon (in as far as has been measured ‘in the lab’, round the 10% mark) but slightly more common in those with more experience. Which seems to suggest that generally, developing expertise and range is useful in developing this ability

· Prompting from people with more experience, in the form of hints, cues, examples and practice in retrieval of analogous situations all can help with transfer. In other words, it can be taught and learnt to varying extents. So seeking advice from people with more experience is one obvious solution…

· People vary in the amount of time they need to ‘digest’ the problem before they can apply their knowledge to the new context.

· The degree of similarity between the new problem and ones previously encountered generally increase the probability of successful transfer.

· Memory and the ability to recall or ‘retrieval’ of previous experience is a factor.

· Purpose - wanting or having to solve a problem can aid the process.

· Rigid mental models can limit the ability to transfer learning. An example could be the fact that some people differentiate starkly between play (or exploration) and learning and think that learning can only take place in teacher directed ‘work’.

· ‘Interleaving’ when in the Practice context – practicing in different environments and mixing in with other similar skills being learnt may help with many of the above factors.

· All these factors need to be kept in mind as having varying effects on people depending upon context.

Are there any other strategies that one could use to increase the ability to transfer Learning? After all we are probably all aware of people (or aspects of ourselves) who are highly educated in some respects, yet who can act extremely foolishly in other contexts.

The use of analogies, to guide transfer in problem solving has been used since antiquity and some practical wisdom traditions have developed a very sophisticated technology of their use. Cognitive psychologists have been doing some research for about 40 years or so, with a recent increase in interest. The Radiation Treatment problem (a patient has a tumour that needs radiation, but the radiation will damage healthy tissue in path to the tumour.) that was used in Studies by Gick and Holyoak in the early 1980’s that showed that some people who struggled to solve the problem initially were able to do so when presented with the analogous story of the General and the Fortress first or when prompted to use the story.

Research into this is still at an early stage, but a summary of the findings to date suggests –

1) The analogies need to be good. For the relatively simple problems that have been studied, this means that –

· The initial and final goal states of the analogy and the problem need to be the same.

· The structure of the relationship between the objects and the constraints needs to be the same in both.

· The solution(s) need to be the same.

· All the above are something close to what we understand as a deeper understanding of a subject being studied.

2) A range of similar analogies can be useful. They need to be easily retrievable, either by active memorisation or by slow absorption from a culture. (There is recent experimental evidence that slow implicit absorption does occur.) Interestingly, the narrative form is useful for both types for entry into memory and has been long used in some practical wisdom traditions.

3) Actively working through analogies, where one is looking for the deeper structural similarities and differences and being able to articulate them can be useful. One way of articulating them is to generate one’s own analogies to describe a situation and monitor them for appropriateness.

The use of analogies has shown promising results in learning in diverse fields but equally it would be less useful to overplay their utility. However, these suggestions could quite easily become part of teaching or learning routines and may be of interest to the reader to explore these themselves. Creating an analogy to represent a situation could quite easily be a micromastery that one could apply in many contexts

One additional benefit and aid to critical thinking that you may find yourself noticing when you begin to become more familiar with analogies, is that many analogies that people attempt to use for persuasion are, to put it politely, not very good! At best, only one of the points in 1) above are the same for both the problem/situation and the analogy, or that the analogy focusses on ‘surface’ similarities rather than structural similarities. Also, the analogies needed for complex situations or problems, (which are often the subject of such unsuccessful persuasion attempts) are of a quite different nature, and which may be better considered in a separate newsletter. Oversimplified or inaccurate analogies can lead quite simply to misconceptions. Talk of persuasion take us neatly to the next potential barrier to learning….

Reactance

Long recognised and described (you can see it in the Odyssey.) It is one of those things that people would know if they saw it. There is a somewhat limited description has been the basis of theory for about 60 years of academic study.

‘An unpleasant motivational arousal that emerges when people experience a threat to or loss of their free behaviours.’

Much of the research has focussed on the feelings of anger and resistance that accompany this response but more recently a wider range of responses has been noted including avoidance, acceptance, ‘passive resistance’, the fact that it can be a source of motivation that is positive in certain contexts and other forms of more measured responses. Likewise, there is a similar recent increase in understanding of how ‘threat to or loss of free behaviour’ can manifest. Rather than only being told that one can’t or must do something or have something, it is now being recognised (particularly the ‘perceived’ threat) as being part of general social interaction, or of certain types of persuasive efforts such as guilt or fear appeals which are seen as or really are manipulative, attempts to control of language and thought, and perceived threats to one’s groups and social identities.

In a learning situation reactance could manifest itself through the content of what is being learned. For example, the content could be threatening to long held and cherished mental models or beliefs. Sometimes content is perceived as ‘too simple for me’ where people have misconceptions about their true needs and what learning is really relevant to where they are. (Or conversely, too difficult for me’.) It could arise from the way something is being taught or learnt (for example the pace might feel threatening) or the social relationship between the ‘teacher’, which might be perceived as cold or superior for example.

There is a brilliant and extremely funny story (that comes to mind as I have recently enjoyed listening to it with my grandson,) called The Outlaws and Cousin Percy from the Just William series, which illustrates some of these perceptions.

It can be inferred that William, and his friends perceive that Cousin Percy is trying to ‘teach’ them with tales of his daring do and good deeds and that the lessons are unwelcome, particularly when his hypocrisy is revealed. William’s response is very controlled and ultimately socially devastating for Cousin Percy.

Are there ways of removing unproductive reactance?

It may depend upon one’s role and context. If one is in a teaching context for instance, one can adapt warm relationships with students, promote as much choice as possible, use explanation rather than commands and so on. This type of advice is readily available. If one is largely directing one’s teaching oneself, one has a lot more control over the learning process than in a compulsory setting and reactance may well be less common. Some of the suggestions in micromastery also mitigate against it too. However, as it may occur on occasion and as it is a very useful life skill (particularly if you consider that learning can occur in any situation,) it could be worth looking at some potential strategies.

Firstly, it is clearly influenced by culture and the resulting self that we construct, so one avenue might be to consider which aspect of one’s personality (or which self) is doing the reactance.

An excellent introduction to thinking about and using the ‘which aspect of yourself may be reacting’, by someone with much experience and expertise in the matter can be found in the following audio download. The author herself skilfully uses a lot of metaphors, analogies and narratives in this description. It has much consonance with a micromastery approach too.

https://www.humangivens.com/publications/which-you-are-you/

In an interesting link with transfer, people with long experience of teaching aver that often, if you tell people directly that they need a certain understanding they are often least able to accept it without an analogy.

Linked to this, can be the practice of taking a step back and consider whether the threat is legitimate or not. Whether it is trivial or not is a good starting point along with reflection on what constitutes trivial for oneself. One aspect of triviality worth consideration is the group of interactions one considers insulting. It may not be particularly fashionable or acceptable now, but some consider most insults to be un-objective and in a sense not real. (If threats are real, it may have to be said, then a response may well be justified.)

Another aspect worth refection is the nature of the response – whether anger and aggression are the only or default responses one has available. William’s response to Cousin Percy is illustrative of the many more subtle or ‘trickster’ reactions shown in long established folk and practical wisdom tales. The Good Soldier Swejk is a more modern funny satirical novel that illustrates the use of (possibly feigned) incompetence as a form of passive resistance.

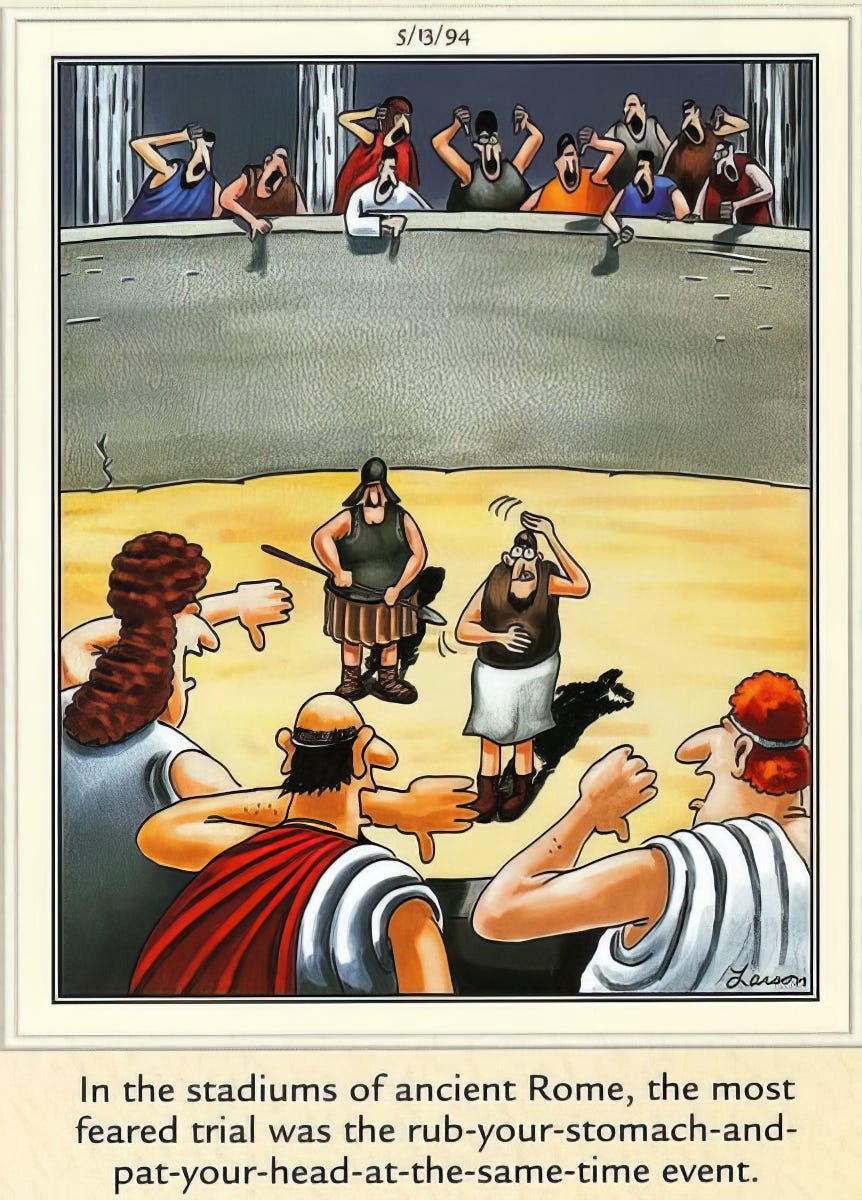

A particular one that the academics have recently rediscovered (and which many parents pick up quickly from experience) is ‘prescribing the symptom’ technique. There are other examples of reverse or paradoxical ‘psychology’ that many of us are aware of that would be relevant. Also, finding humour (from both sides as it were) has long been acknowledges as very useful at taking the heat out of such situations.

Over these last three newsletters, how we can, sometimes, ‘get in our own way’ of learning has been described. The models we can have created or learnt about learning themselves have an influence and a potentially more useful model has been suggested. How we respond emotionally to levels of challenge, modifying our models of the world as we learn, assessing our progress, trying to transfer our learning and potential reactance to learning have been described.

In a sense, the ‘worst case scenario’ has been presented and to avoid engendering unwarranted pessimism it is worth remembering that we don’t all fail at all these challenges all the time!

We do learn – all the time, and we are overcoming these barriers too. One of the purposes of this newsletter is to is to make that natural ability to learn stronger by ‘learning how to learn’ and one aim of the newsletters is to be a reference that one can go back to if one finds oneself getting a bit stuck or on the plateau to see if there is a particular barrier acting at that particular time and context. It is not a list of everything that can or will go wrong!

There is another aspect that hasn’t been mentioned, that of modulating one’s attention when learning. That that will be folded into a subsequent newsletter which will have some fun flipping the perspective and looking at what it is that teachers actually do. And then ask questions about what learners could possibly take on for themselves from that role.

********

Finally, some advice on writing from Rob -

If you are writing a story try thinking of yourself as an enchanter rather than a story teller.

My dear husband of 58 years just died. My first experience of death up front and very personnel. Much of my past positive experience has had to kick in and be wiling to listen to others with more experience of death than myself. This was a new test. I am surprised at many of my reactions, some quite animal, some objective, some very emotional. I often now hear my husband's voice as if his experiences have somehow become mine. His good advice comes at me when getting too emotional. Also, I have STORIES which I read or have read and they come to mind, many which now fit in to this new experience whereas before I wondered if some ever would, if you see what I mean. It is good to have a whole wealth of stories to call on. What I also have is a firm belief that my husband is back where he belongs wherever that is. At death, he looked so calm, so peaceful, so beautiful, as if he had just put his hand in the hand of God and was whisked away, transformed somehow. One of my oddest reactions was to look back at our life together and to be overwhelmed by how quickly our 58 years seemed in hindsight. Life is fleeting. Use every second, every minute to keep learning, but also to relax and be glad in all that you may have already learned and to keep going no matter what and have fun. Love is becoming more understandable to me. And one last thing. I think all my Micromastery of organising projects like seminars, lectures, club events, stalls for different groups, being a reluctant leader, have all kicked in when organising my husband's Funeral and now his Ashes' Interment. I know this sounds odd. Also, when death of a loved one hits you, a huge amount of intuition is needed. Let your Intuition get a grip when needed and follow it. Close Death is an experience which covers all parts of the brain, I think.

How to Develop Analogies (This is based on two tables - one for Target and the other for the Base domain that could not be attached here - if anyone would like a copy e-mail kcbyron2@gmail.

1. Describe in a few words, the abstract idea (Target Domain) you wish to communicate by analogy.

2. Brainstorm a few characteristics, features or mechanisms of this abstract idea.

3. Moving to the ‘Base Domain’, and without having any specific Base (Analogy) in mind,

write up to 3 different random analogical associations you have with each of the Target characteristics.

4. When you have sufficient associations for each of the Target characteristics, scan through them and see if there are words that appear more often than the others in the analogical associations. Use this as your ‘Selected Base Domain’

5. Write a few notes summarising the selected Base in terms of the Target characteristics. Finally write a couple of sentences describing the original Abstract Idea in terms of the selected Base analogy that you could use. Note: It’s useful to check the limitations with the analogy, and test it out with your colleagues.